The new Motus tower installed at Audubon’s Lea Island sanctuary this spring is already picking up the signal of radio-tagged birds migrating long distances to reach the North Carolina coast, and a few of them have something in common. Three of the first four birds detected by the tower this summer were Short-billed Dowitchers tagged by the same researcher in the same remote boreal wetlands in Canada.

Olivia Maillet, a graduate student at Trent University in Ontario, spent the spring tracking down these plump, robin-sized shorebirds in their watery, grassy breeding grounds in the Hudson Bay Lowlands near Churchill. It’s hard work; the nests are hidden in vegetation and the birds don’t flush easily, making them difficult to catch. By the end of the field season, Maillet had tagged 15 birds.

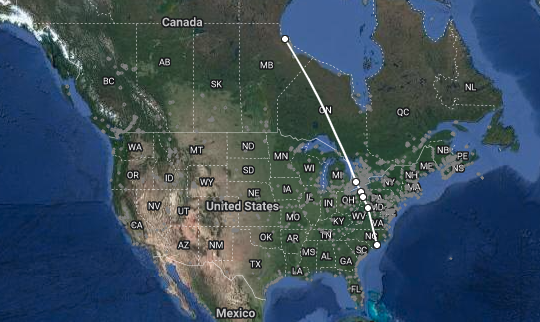

Because of the new Motus tower at Lea Island, we now know that three of those dowitchers—birds that nested within 800 yards of each other in Canada—made the same 2,000-mile journey over just a few days, traveling to the undeveloped barrier island, located north of Wilmington.

“Twenty percent of tagged birds all migrating through the same place is pretty incredible,” said Erica Nol, biology professor at Trent University and supervisor of the shorebird surveying project. The birds made the cross-country trip separately, and were detected at different dates and locations along the way.

Difficult to Study

Short-billed Dowitchers are rusty-breasted in their breeding plumage, with long bills (despite their name), not exactly inconspicuous birds. But they are a relatively under-studied species, in part because of their remote breeding grounds. The first nest wasn’t discovered until 1992, Nol said.

“We don’t really know much about Short-billed Dowitcher migration, except what you can see from eBird,” Nol said. “We don’t know much about migratory connectivity, which birds go where.”

The radio-tagging project is already helping shed new light on these questions. In turn, the data can help us better understand the places that are most important to dowitchers and other shorebirds.

“Any time you get a high proportion of a bird population bunching up in one place, it makes them more vulnerable, but it also presents an opportunity,” said Lindsay Addison, coastal biologist at Audubon North Carolina. “It gives us a clear picture of the places we need to protect.”

Addison and her team manage Audubon’s Lea Island Sanctuary, monitoring nesting bird colonies in the spring and summer and conducting bird surveys throughout the year. During migration, the island’s natural inlets and mudflats provide foraging grounds for migrating species, including Maillet’s three long-traveling dowitchers.

Experience Shorebird Migration

The Lea Island Motus tower was installed as part of a partnership between Audubon North Carolina, Cape Fear Audubon Society, and UNC Wilmington’s Danner Lab. Two other towers installed by the North Carolina Coastal Reserve and the Bald Head Island Conservancy in partnership with the Danner Lab are further helping to detect migrants in the Cape Fear Region. (A fourth dowitcher tagged by Maillet was detected by the tower at Masonboro Island, just 15 miles south of Lea Island.)

As shorebird migration ramps up across North Carolina and the country, birds are making similar voyages, connecting dots on the map from Canada to Argentina. For the most part, these journeys take place out of sight. But new tracking efforts, like the Motus network, are giving us an unparalleled glimpse into their movements. Motus data is available to the public, and you can explore the website to view the species that are passing by specific towers or the travel routes of individual birds.

For birders experiencing FOMO on this phenomenon: You don’t have to travel to a remote barrier island to get a glimpse of shorebird migration. Sandpipers, plovers, and, yes, dowitchers can be found on lakes, reservoirs, and impoundments throughout much of the state this time of year. Find recent sightings via the free Audubon Bird Guide app: Simply search for the species you want to see, and click the Sightings tab.