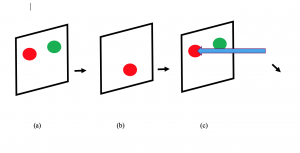

The purportedly simple task called “match-to-sample” seems straightforward and forms the basis of many more advanced types of studies. In the picture to the right, the subject first sees a red and a green circle (a). After a short delay, that screen disappears, and another with only one circle appears (b). After another short delay, that screen is replaced by the original stimulus. If the subject taps the matching color (c), it gets a reward. Sounds simple, right?

The purportedly simple task called “match-to-sample” seems straightforward and forms the basis of many more advanced types of studies. In the picture to the right, the subject first sees a red and a green circle (a). After a short delay, that screen disappears, and another with only one circle appears (b). After another short delay, that screen is replaced by the original stimulus. If the subject taps the matching color (c), it gets a reward. Sounds simple, right?

Well, not very. Before anything even begins, the experimenter must make sure that the subject—say, you or your parrot—can distinguish the two colors. Some nonhumans (and humans!) are somewhat color-blind, others—like parrots—see in the ultraviolet. Thus, for the parrots, the “red” and “green” might not actually look like what you and I see as red and green, but the two colors will look different enough for the purposes of the experiment. That isn’t true for all subjects, so some knowledge of the subjects’ visual system must be obtained initially.

Experimenters also have to make sure that the subject doesn’t like one color more than the other so that the subject doesn’t come into the experiment with some kind of preference, which would skew the results. Ditto for a side preference—if for some reason (say, you are left-handed), and you like to tap the left circle more, that would also skew the results.

Everyone Likes Rewards

Subjects will also probably have to be taught to tap something for a reward: If I sat you in front of a computer screen with those two circles on it, and gave you no direction—no mouse, no keyboard, just the screen—would you know what to do? At first, I’d have to wait however long it took until you chose to a tap on a circle before I could give you a reward; then, in order not to skew the results, I’d have to reward you for learning to tap both colors and make sure that you are tapping both equally (again, to avoid any preferences)—but of course that teaches you to tap both, which is not what I want you to do eventually. But let’s assume that you are now tapping both colors equally and we start the experiment: After seeing both circles, your screen blanks and the single circle appears, which then disappears and the original screen returns…what should you do? As it turns out, it takes most subjects at least a few trials to figure out what is being tested—to tap the correct “match” and to unlearn the need to tap both circles equally.

Subjects will also probably have to be taught to tap something for a reward: If I sat you in front of a computer screen with those two circles on it, and gave you no direction—no mouse, no keyboard, just the screen—would you know what to do? At first, I’d have to wait however long it took until you chose to a tap on a circle before I could give you a reward; then, in order not to skew the results, I’d have to reward you for learning to tap both colors and make sure that you are tapping both equally (again, to avoid any preferences)—but of course that teaches you to tap both, which is not what I want you to do eventually. But let’s assume that you are now tapping both colors equally and we start the experiment: After seeing both circles, your screen blanks and the single circle appears, which then disappears and the original screen returns…what should you do? As it turns out, it takes most subjects at least a few trials to figure out what is being tested—to tap the correct “match” and to unlearn the need to tap both circles equally.

Note that even if subjects guess correctly on the first trial and get a reward, it doesn’t mean that the subjects will act the same way on the second trial—they might want to try to find out what happens if they make several different choices. Now, in my lab, we would skip most of these steps by simply demonstrating what we want our birds to learn—by having a bird sit on a perch while two trainers sit in front of the screens that appear and disappear, showing what should be tapped—but we still have to worry about color and side preferences. And that is just for the basic step in many tasks! You can begin to see what is involved.

For some tasks, like studies on object permanence, where we are testing whether subjects understand that something still exists even if they can no longer see it, we hide things in one of several places and then ask them to find it—and thus have to make sure that they can’t tell where the object is through inadvertent cues. One such cue is scent. Even though we think that parrots’ sense of smell is about as good as ours (i.e., not very good), we can’t be sure, so we have to control for possible scent cues. This issue would be especially important for subjects like dogs, that are really good at scent detection.

We also have to make sure that we touch all the different possible sites after we hide the object and before we let the birds make a choice, to ensure that they aren’t just going to—or avoiding—the last place we touched, as another cue. And we have to make sure that we aren’t cuing them by gazing at the correct spot. Parrots don’t track our eye movements at a close distance, so that’s not usually a problem, but they can track our head movements, so we have to be careful to stare downwards or straight ahead when they make their choices. Of course, other species might be able to track eye movements. Again, you start to see some of the possible subtle issues…and even how the species that is being tested affects the issues.

For some tasks, we have to find two different treats—whether food or toys—that the birds like equally well—something that is not always easy to do. Occasionally that is just impossible, so we show the birds that they can ask for some favorite treat if they’ll play along and choose or identify something that isn’t particularly attractive or fun for them. It often takes a long time for them to agree to work under that condition.

Then there are issues such as “expectation cuing”—something that can occur when the subjects experience many trials on the same topic in a row, so they “expect” that the answers will involve a particular type of response, like a number or color label, and therefore ignore all the other possible answers, which significantly simplifies the task. That is why we do lots of different types of tests all at the same time.

I’ve tried to provide just a sampling of just some of the types of issues that are involved when one is trying to determine the various abilities of nonhumans. Many others exist, but even from this short essay, I hope you can see that the task of designing an experiment is never simple!