iCatCare Feline Wellbeing Panel (FWP) member Esther Bouma shares with us her thoughts on her latest published research on owner relationship perceptions and the consequences for cats.

Why did you want to study the perception of the human-animal bond?

Many studies have examined the benefits of animals for humans, but there has been much less study on how living with people benefits companion animals. Companion animals can function in roles similar to humans, such as providers of social support and companionship or objects to fulfil our human need to nurture and care. The overarching goal of our research is to study how social roles of companion animals are intertwined with owners’ perceptions of both the relationship as well as the animal itself, and how this influences the wellbeing of the animal.

Which aspects of the cats’ living environment were studied?

We examined aspects that were related to feline welfare and were likely to differ depending on the owner’s relationship perception – such perceptions were categorised as ‘family member’, ‘best friend’, ‘child’ or ‘pet animal’.

We examined outdoor access, access to the bedroom, and care during owner absence. Access to the outdoors has both beneficial effects (as it reduces boredom, frustration and obesity) and risks (such as accidents, poisoning and infectious diseases). In the Netherlands it is common for cats to have (restricted) outdoor access. Access to the bedroom is also common as a previous study showed that two-thirds of pet cats are allowed in their owner’s bedroom. Consistent access to the bedroom provides the cat with a continuously accessible place for a quiet nap or a safe hideout. In the Netherlands, most owners leave their cats in the care of friends and neighbours with variable quality of care. Some owners hire a professional cat sitter or bring their cat to a boarding facility. Although some cats do not seem to mind staying in an unfamiliar environment, most cats show less stress related behaviours in their own territory.

We formulated several hypotheses for each of the four relationship descriptions in relation to the aforementioned markers of the living environment which can be found in the Introductory section of our paper.

Can you tell us something about your methods?

Participants filled out an online questionnaire. If participants owned more than one cat, they were asked to keep one specific cat in mind when answering the questions. A large cross-sectional sample of 1,859 Dutch cat owners was presented with four relationship descriptions: ‘pet animal’, ‘family member’, ‘child’ and ‘best friend’ (of which the last three are considered anthropomorphic perceptions) and asked to choose which description fits best. Owners could also choose the option ‘It is difficult to describe the relationship with my cat’.

First, we examined the influence of factors related to the owner (such as social living environment, age, gender, education) the cat (such as being a pedigree, being the owner’s first cat, and owner-directed behaviours), and the owner’s perceptions of their cat (for example related to support, empathy, loyalty and dependency) on the owners’ choice of a particular relationship description. Then we examined if the living environment of the cats differed between the four relationships descriptions.

How did Dutch cat owners perceive the relationship with their cat?

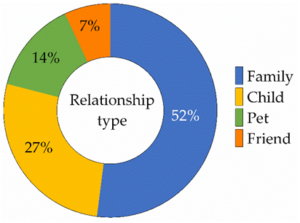

In our sample of 1,859 cat owners, over half see their cat as part of their family (n=943, 52%) and more than a quarter as their child (n=493, 27%). Fewer owners see their cat as a pet animal (n=258, 14%) and the lowest proportion sees their cat as their best friend (n=109, 7%).

Which cat-and-owner factors influenced relationship perception?

Owner’s age, presence of other adults in the household, the cat being a pedigree and owners’ agreement with their cat’s equality to humans, dependency on them, and provision of social support were significantly related to relationship perception.

Owners’ gender, educational level, cat-related profession or agreement with statements about the cat’s companionship, empathy and loyalty, being the owners first cat, duration of ownership, the cat’s gender, and behaviour towards the owner were not of influence.

How did the living environment of cats differ?

Cats of owners who see them as a child or best friend are allowed significantly more often in their owners’ bedroom. Although sleeping on the bed with the owner is also slightly more prevalent in these groups, the overall group difference was not statistically significant after correction for multiple testing.

Outdoor access is most common in cats that are seen by their owners as pet animals or family members. Cats in the pet animal group are the least restricted in their whereabouts. Most have a cat flap that is open at all times. Cats in the best friend or child group that do have access to the outdoors often have no control over time and duration and are often only allowed in a fenced garden or catio. When away for several days, owners in the pet animal group leave their cat more often in the care of friends or neighbours. Owners in the child and friend group more often indicated that they didn’t leave the house for several days. Lastly, owners in the child group have more cats. Cats of owners who see them as a pet animal or best friend have the highest likelihood of being the only cat in the household.

Do owners who see their cats as pet animals anthropomorphise their cat less?

Our findings suggest that owners who describe the relationship with their cats in an intimate social human role such as a child or best friend anthropomorphize their cats to a higher extent than owners who see them as pet cats. Owners in the pet animal group agreed the least with statements about their cat being supportive, empathic, equal to humans, loyal and dependent on the owner for love and care, while owners in the best friend and child group agreed the most. Owners who describe the relationship with their cat as being similar to a child, display behaviours similar to human parents towards their children; namely (over)protection and provision of (exclusive) care.

How can anthropomorphic perceptions be detrimental to feline welfare?

Owners who perceive their cat as a small human might misinterpret their (subtle) behaviours or exaggerate their social abilities. Attribution of social abilities such as ‘perceptive’, ‘empathetic’ and ‘considerate’ makes it possible for animals to be a source of support. But as descendants of solitary hunters, the social skills of cats might be less evolved than in group-living animals such as humans and dogs (for whom social skills are necessary for survival). Looking at a cat from a human perspective can result in a miss-match between the need of the owner and the need of the cat.

For example, humans display their affection by hugging and cuddling but being held tight is for (most) cats not pleasant. And although many cats enjoy petting, the duration and body parts that are touched are often not compatible between the preference of cat and owner. Lastly, while owners (with the best intentions) want to protect their cats from the dangers of the outside world, they might deprive their cat from their natural drive to explore and play/hunt. The welfare of indoor cats might be compromised when the living environment is suboptimal (small, multiple cats, limited resources and absence of environmental enrichment such as food puzzles or (scented) toys).

Which cat has the ‘best cat life’?

That is difficult to answer as we did not examine the environments by means of a qualitative checklist or home observations. We see that the most pronounced differences are between the pet animal group and the three ‘anthropomorphic’ perceptions. Cats in the pet animal group have less access to the bedroom but they often have unrestricted access to the outdoors. About one fifth of owners from the best friend and child group do not leave the house for several days/night which may or may not be beneficial for the cats, depending on how the cat interacts with them and how they perceive their owner. As descendants from solitary animals, cats in the best friend and pet animal group have the highest likelihood that they don’t have to share their household with other cats while cats of owners who see them as children often (have to) share their (indoor) environment with other cats.

Why are the results interesting for owners?

We hope that our results make owners more conscious about their own (social) needs and how these influence the living environment and wellbeing of their cats. Owners who want to protect their cats from outside dangers should be aware that the welfare of their cats might be compromised when the indoor environment is suboptimal. Moreover, although domesticated cats can live in close proximity to each other, the presence of other cats can either be pleasant or stressful, depending on the number of cats, the size of the living area, access to resources and the quality of the relationships between the cats.

Why are our results interesting for cat professionals?

Recognising owners’ vocabulary when they speak about their cat might reveal the cats’ social importance for the owner. Recognising the cats’ social role might stimulate effective communication with owners. Our results suggest that owners who see their cats as best friends or children might attribute biologically invalid abilities to their cats. Providing information about the natural behaviour and welfare needs of cats might benefit feline welfare.

To help all cat carers understand more about cats and what keeps them physically healthy and mentally well, we have a vast advice section on our website covering an extensive range of topics from general care to cat health, safety, handling and problem behaviours, to name just a few, visit https://icatcare.org/advice/

Bouma EMC, Reijgwart ML, Dijkstra A. 2021. Family Member, Best Friend, Child or ‘Just’ a Pet, Owners’ Relationship Perceptions and Consequences for Their Cats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19(1), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010193

I am the feline behaviour specialist at feline charity ‘International Cat Care’. We are about engaging, educating and empowering people throughout the world to improve the health and welfare of cats by sharing advice, training and passion.