Our model-rival (M/R) technique is almost always successful in training our parrots to acquire novel labels for objects, actions, attributes, and concepts. (Of course, whether they will subsequently use the labels is a matter of choice: Alex did so constantly, whereas Athena will talk only when absolutely necessary—e.g., when she knows Griffin will get all the green beans unless she pipes up!) When success is elusive, however, some theories and experiments with children often explain the reasons. An interesting example was when Griffin, unlike Alex, couldn’t seem to learn to use his color labels to describe objects. The issue was something called mutual exclusivity.

Mutual Exclusivity in Children

The term describes the behavior of children who, in the process of learning language, may persist in exclusively using the first label that they learn for a given object, and thus have difficulty acquiring additional labels for this item (Liittschwager & Markman, 1991, 1994). They function under the assumption that every object has a label—and only one. Having learned, for example, to refer to their pet as a doggie, such children will often refuse to use any other label for that creature; that is, they will actually insist, “NOT animal, doggie” (see Merriman, 1991). Specifically, they have problems understanding how categories can overlap. Although this may seem like a serious issue, at that stage in acquisition, it actually helps them learn new labels. Thus, given two objects, one whose label is known (e.g., block) and another whose label is not (e.g., tongs), a child using mutual exclusivity will, after hearing the novel label tongs, exclude it from the familiar, already labeled item and assign this new label to the new, unlabeled item (e.g., Tomasello & Akhtar, 1995).

This process is also sometimes called fast mapping (see Carey, 1978), although it often takes the child a while to use the new label appropriately. Eventually, as children develop additional language skills this process is extended to other types of label acquisition (see Markman, 1994); for example, if children are given two balls—that they easily label ball—one red and one an odd greenish-yellow color, and are told to pick up the chartreuse thing, they quickly figure out that the new weird label is a color.

A Parrot’s Grasp of Mutual Exclusivity

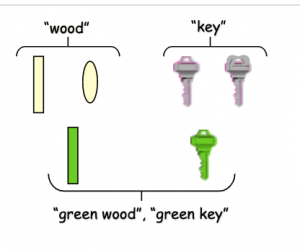

These findings made us think about the slightly different ways in which African greys Alex and Griffin were taught their object and color labels, and how mutual exclusivity could explain the differences in their subsequent behavior. First, let’s look at Alex. We started with objects that had no real color—for example, white strips of paper, pieces of wood like tongue depressors, silvery keys. He learned to identify them respectively, as “paper,” “wood,” and “key.” A clothespin was labeled “peg wood.” After he could accurately label these objects, as well as “hide” (pieces of rawhide chew toys), we introduced the color “green,” using it not as an alternative label, but as an additional label—so we modeled “green wood” and “green key.”

These findings made us think about the slightly different ways in which African greys Alex and Griffin were taught their object and color labels, and how mutual exclusivity could explain the differences in their subsequent behavior. First, let’s look at Alex. We started with objects that had no real color—for example, white strips of paper, pieces of wood like tongue depressors, silvery keys. He learned to identify them respectively, as “paper,” “wood,” and “key.” A clothespin was labeled “peg wood.” After he could accurately label these objects, as well as “hide” (pieces of rawhide chew toys), we introduced the color “green,” using it not as an alternative label, but as an additional label—so we modeled “green wood” and “green key.”

If the object had no color, he was to respond “wood” or “key,” but if it were colored, he had to produce both labels, “green wood” or “green key.” We used two different objects so that he would recognize that the attribute and label could be used with multiple items. It took some time for him to learn to produce the new sounds (although he had the “eee” from “key”), but he then quickly learned to add the label when asked about the newly tinted items and even transferred the label fairly quickly to “hide”: Although he initially called it “hide,” he attained an accuracy of 60% correct (“green hide”) after only 5 min with the M/R procedure. That is, out of seven presentations immediately following training, he correctly labeled the object “green hide” four times and incorrectly labeled it “hide” three times (Pepperberg, 1981). His accuracy improved rapidly, and he subsequently learned other color names, also as additional labels, without any problem. He did not engage in mutual exclusivity.

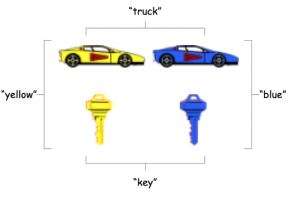

Griffin, however, was taught very differently (Pepperberg & Wilcox, 2000). Griffin’s experiences with objects were designed to resemble more closely those of small children. Instead of the uncolored items Alex first encountered, Griffin’s objects—wool pompons, bits of paper, toy cars (called truck), and so forth—varied in color and size; only corks were uncolored. Thus, he had a more complicated task than Alex had been given. For example, during initial training, he had to recognize that truck was the common term to describe variously colored and shaped toy cars.

Griffin, however, was taught very differently (Pepperberg & Wilcox, 2000). Griffin’s experiences with objects were designed to resemble more closely those of small children. Instead of the uncolored items Alex first encountered, Griffin’s objects—wool pompons, bits of paper, toy cars (called truck), and so forth—varied in color and size; only corks were uncolored. Thus, he had a more complicated task than Alex had been given. For example, during initial training, he had to recognize that truck was the common term to describe variously colored and shaped toy cars.

His color training also differed from Alex’s. He was first trained on color labels (rose, green, yellow, orange, blue) by two humans using a computer display (colored circles on a white background) as part of a separate study on how the inability to interact with physical objects might affect label acquisition. And, unlike Alex, he was not required to produce both color and object labels for a colored item; rather, he had to respond with a single label to “What color?” versus “What toy/matter?” The goal was to see whether these differences affected his pattern of learning and eventual success. Once he had acquired several color and object labels, we then queried him about the colors of objects he could already label (“wool” pompons) and items he was simultaneously learning to label (a plastic “cup”). Might he use labels differently in the two cases? And if he did, would he exhibit mutual exclusivity. That is, refuse to use the color label for the object he already knew as “wool” but not for the one he could not quite yet label as “cup”?

And that is exactly what he initially did (Pepperberg & Wilcox, 2000). Although he eventually did learn to use color labels (and later shape labels) appropriately for objects for which he had initially learned material or toy labels, he took many sessions and considerable extra training to do so. The reverse was true for objects for which he first learned color labels, although, again, he eventually learned their object labels as well. What is also of interest is that children who are taught multiple labels are a bit more like the way in which Alex was taught, where multiple labels are introduced in a complementary manner (“This is a kitty; a kitty is a kind of animal” do not exhibit mutual exclusivity (see Gottfried & Tonks, 1996).

Many reasons have been proposed for why any organism might engage in mutual exclusivity (see references in Pepperberg & Wilcox, 2000). The interesting point is that both parrots and humans, separated by over 300 million years of evolution, can exhibit very similar learning strategies!

References

Carey, S. (1978). The child as word learner. In Linguistic Theory and Psychological Reality; ed. M. Halle, J. Bresnan, and A. Miller, pp. 264-293. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Gottfried, G. M., & Tonks, J. M. (1996). Specifying the relation between novel and known: Input affects the acquisition of novel color terms. Child Development, 67, 850-866.

Liittschwager, J. C., & Markman, E. M. (1991, April). Mutual exclusivity as a default assumption in second label learning. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Seattle, WA.

Liittschwager, J. C., & Markman, E. M. (1994). Sixteen- and 24-montholds’ use of mutual exclusivity as a default assumption in second-label learning. Developmental Psychology, 30, 955-968.

Markman, E. M. (1994). Constraints on word meaning in early language acquisition. Lingua, 92, 199-227.

Merriman, W. E. (1991). The mutual exclusivity bias in children’s word learning: A reply to Woodward and Markman. Developmental Review, 11, 164-191.

Pepperberg, I. M. (1981). Functional vocalizations by an African Grey Parrot (Psittacus erithacus). Zeitschrifl fiir Tierpsychologie, 55, 139-160.

Pepperberg, I. M., & Wilcox, S. E. (2000). Evidence for a form of mutual exclusivity during label acquisition by Grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus)? Journal of Comparative Psychology, 114, 219-231.

Tomasello, M., & Akhtar, N. (1995). Two-year-olds use pragmatic cues to differentiate reference to objects and actions. Cognitive Development, 10, 201-224