As those of you who have been following this blog know, many entries describe the research studies in my laboratory, which usually involve comparisons between African grey parrots and other nonhuman subjects, or between African grey parrots and young children. Most of the time, the methodology of a study needs very little adaptation from the original work with humans or other primates, as the tasks are generally designed for children with limited vocabularies or require simple actions, such as pointing, where a beak works just as well as a finger. Sometimes, however, there are studies we just can’t seem to adapt.

As those of you who have been following this blog know, many entries describe the research studies in my laboratory, which usually involve comparisons between African grey parrots and other nonhuman subjects, or between African grey parrots and young children. Most of the time, the methodology of a study needs very little adaptation from the original work with humans or other primates, as the tasks are generally designed for children with limited vocabularies or require simple actions, such as pointing, where a beak works just as well as a finger. Sometimes, however, there are studies we just can’t seem to adapt.

Some Successful Studies

On the plus side, we’ve been able to examine how the birds compare with children and nonhuman primates on many Piagetian and related tasks. The birds score exceedingly well on tasks such as object permanence (remembering the placement of a hidden object; Pepperberg & Kozak, 1986; Pepperberg et al., 1997), on liquid conservation (knowing that the amount remains the same whatever container is used; Pepperberg et al., 2017; Cornero et al., 2019), and probability studies (figuring out the likelihood of a specific event; Clements et al., 2017). They also do well on inference by exclusion (figuring out where something is hidden after being given some information on where it can’t be; Pepperberg et al., 2013, 2019). Overall, the parrots match or outperform nonhuman primates and children up to about 6 or 8 years old, depending on the task.

We’ve also been able to compare the parrots to adult humans on tasks examining how they literally see the world and evaluate actions in the world. By asking them to label what they are perceiving, we find that, despite having visual systems that are quite different from those of humans, they evaluate common optical illusions just like human adults (Pepperberg et al., 2008; Pepperberg & Nakayama, 2016). By asking them to track the motion of hidden objects, we find that they are also very similar to adults with respect to what is known as visual working memory (Pailian et al., submitted).

For Parrots, How To Catch Without Hands?

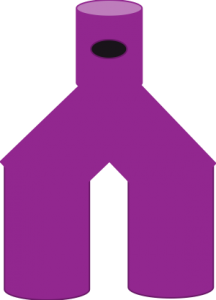

But what happens when a subject needs two hands to solve a problem? My colleagues have designed a fascinating study to examine the age at which young children and nonhuman primates figure out how to simultaneously prepare for two mutually exclusive versions of a single future event — specifically, how to catch a reward that is dropped into an inverted Y-shaped tube with one opening at the top and two possible exits at the bottom (see above). The task is important because it demonstrates the ability to plan for the future and thus solve a problem that cannot be figured out by physical trial-and-error.

Adults look at the system and immediately put one hand under each of the two bottom openings. It turns out that children must be about 4 years old to figure this out on the first trial; chimpanzees and younger children need many, many trials before they come up with a solution, and often still do not use the two-handed solution consistently. The children and the apes are, of course, first shown how a reward falls down a single tube to make sure that they understand how gravity works and how to place their hand under the opening to get the reward.

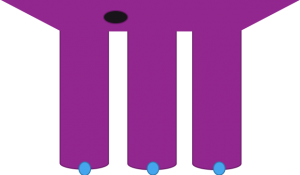

To ensure that the 4-year-olds are not merely making an association between a hand under a tube and getting a reward without understanding the actual task, they are also given a three tube system and shown that one of those tubes doesn’t have a hole at the top; they still pretty much figure out where to place their hands. Given how well our parrots do on all sorts of tasks that stymie children well beyond the age of 4, this task really intrigued us. But how could a parrot possibly come up with a solution? They can’t do the two-handed trick….

Thinking Of Possible Solutions For Parrots

We’ve thought about some kind of system where the birds learn to peck at a button in the single tube system that triggers a mechanism to catch the reward; if they didn’t press within, say 10 seconds, the reward would fall down into an inaccessible trough…Once they figured that out, we would then use a slightly longer delay for the forked tube before the treat dropped into one side or the other — a delay long enough for the bird to have a chance to peck at buttons on both sides.

The birds could the also be given the three-tube task as a control with three buttons. If they understood the game, they would peck at only two of three buttons. But would this system really be testing the same level of intelligence? It isn’t really clear. The children actually talk through and even demonstrate the actions that they expect to happen. They can be seen to simulate the variations in the task, by using their fingers to track the paths that they think the reward will take. The birds can’t do this. And, even if the parrots are correct on the very first trial, one can argue that they are simply making associations between buttons and functional tubes.

We would probably have to give apes and/or 3-year-old children the same task as the parrots. If the subjects that had failed on the original apparatus now succeed on this apparatus, then clearly a difference exists between the apparati that makes one simpler than the other. If the apes and younger children still failed, but the parrots succeeded, then we might be able to claim at least that the parrots had performed better, even if we still didn’t really know what they did or did not understand.

Whether or not we actually ever do this task as I propose — or figure out a better system — you can see the challenges that we face when trying to design various studies for our parrots!

References

Clements, K., Gray, S.L., Gross, B., & Pepperberg, I.M. (2018). Initial evidence for probabilistic learning by a Grey parrot (Psittacus erithacus). Journal of Comparative Psychology. 132:166-177.

Cornero, F.M., Harstfield, LA., & Pepperberg, I.M. (2019). Piagetian liquid overconservation in Grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus). Journal of Comparative Psychology .doi:10.1037/com0000209